Northern Food Retail Data Collection & Analysis by Enrg Research Group

Table of contents

Executive Summary

The purpose of this study is to provide an analysis of the northern Canadian grocery retail system and the environment that Nutrition North Canada (NNC) works within. In addition, the analysis considers how the delivery of the NNC program influences the northern grocery industry.

The focus of this study is grocery retailing across 103 northern communities currently eligible for either the full or partial NNC retail subsidy. Ten communities are singled out for more in-depth data collection and inquiry that is done through in-person visits into the communities. Profiles of the communities are provided as an annex to this report.

The total population of the 103 communities is approximately 93,700, based on the most recent census data available. This population is spread across over 4 million sq. kms. of Canada's North. Most communities contain less than 1,000 inhabitants.

The NNC program is structured to serve communities that lack year-round surface transportation (i.e. no permanent road, rail or marine access). By virtue, these communities are located in remote areas of Canada and a great distance from southern commercial centres where grocery resupply activities originate.

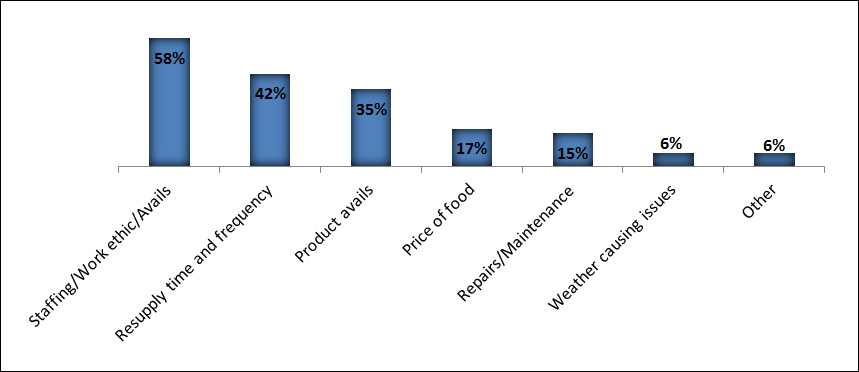

Within this environment, the retailing of groceries is a more expensive undertaking than is the same activity in the South. Northern grocery retailing costs are driven by:

- Transportation;

- Bricks and mortar - cost of maintaining stores in remote communities;

- Human resource considerations - Staffing is a challenge in the North with increased recruitment, training and salary costs;

- Spoilage (losses during transport or Best Before Date expiration) and/or shrinkage (theft). These occur at higher rates than in the South;

- Much higher inventory costs in the absence of 'just in time delivery’ resupply service which is commonplace in the South and

- Retailer profit margins.

The cost of groceries in NNC communities must be placed in the context of the economic situation of many of the local inhabitants. Employment opportunities are very limited. Most families live on single or fixed incomes supported mainly by government assistance.

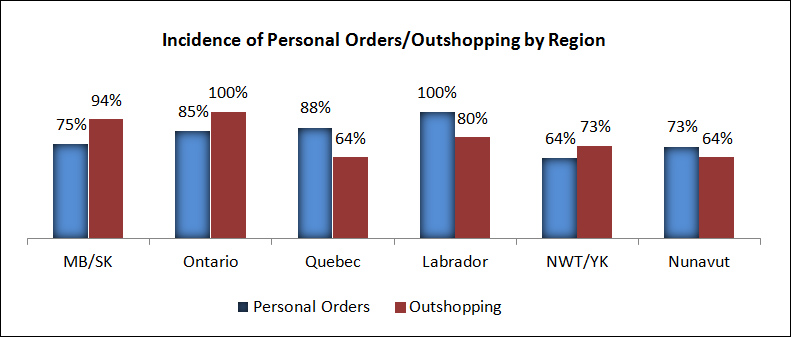

Northern residents are actively seeking ways to minimize the cost of groceries in their communities. Those who reside in communities that have more affordable seasonal transportation service (winter roads or ferry) and some financial resources leave their communities to shop at a southern store.

Consumers unable to leave the community to shop may access the services of suppliers that will fulfill personal orders for northerners and transport orders directly into communities. The air freight distance in Nunavut and Nunavik makes this an expensive undertaking. This service is more broadly accessible in communities across the northern regions of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario.

A range of eligible and non-eligible grocery items are able to be purchased through personal orders. The availability of the NNC subsidy is an important measure to improve the affordability of this form of grocery shopping outside the community. Generally, northern residents are more likely to purchase perishable goods from sources within the community, because the local retailer appears better equipped to ensure quality control on perishable imports.

Local residents often turn to country food (wild game) to manage and budget their household grocery needs. However, there are challenges with the ongoing reliance on wild game to supplement northern diets. The desire among young residents (the 'next generation') to hunt wild game foods appears to be diminishing. In addition, the sustainability of wild game in the quantities necessary to support local communities is questionable, given the higher than average population growth rates.

The prospect of selling country foods in northern grocery stores is complicated by food safety regulations and transportation challenges.

Northern retailers understand that the cost of groceries presents a challenge to local residents of the communities in which they operate. From their perspective, they are continuously looking for ways to find efficiencies in the supply and operation of their stores.

The introduction of the NNC program has helped, because retailers are encouraged to seek out the most efficient means to transport non-NNC-eligible products, while supporting the transportation of perishable products. Stakeholders generally report that the program has resulted in NNC eligible products, particularly highly perishable items, are sold at a reduced price. However, many factors contribute to food security challenges in the North, and the NNC program cannot be called upon to alleviate all of those circumstances.

Observations and Recommendations

Food retailing in the North is the manifestation of an extremely complex supply chain, charged with delivering perishable products to widely distributed communities that are located in difficult terrain and challenging climate. This report provides a number of observations and recommendations to respond to the economics of providing perishable, nutritious food to the North.

Observations & Recommendations regarding the NNC Program

Observation 1: The overarching observation from this study is that food security and nutrition in the North is extremely variable and "one size may not fit all." Also, as suggested by one health care professional, the solutions to nutrition and food retailing challenges in the North are "intergenerational," and will take "decades." This individual meant it will take concerted efforts to expose school age children to healthy eating options from a 'southern' food or 'grocery store' food prospective.

Northern residents, like individuals from the South, learn many of their eating and cooking habits from their parents. In far northern communities, these efforts have to begin with school age children so this generation develops the skills to navigate the wide array of food options in a grocery store—and hopefully, navigate in a healthy manner. In the more remote communities, complex cooking-from-scratch skills are not yet common among certain segments of the population.

Observation 2: Many healthy eating and food preparation education programs are being offered in northern communities. Some of these are general in nature, while others are more focused on addressing specific health concerns such as diabetes.

Recommendation: Unquestionably, these educational programs and others like them provide valuable information and assistance to local residents regarding healthy eating and meal preparation. Based on interviews and observations, opportunities exist to inform people about the NNC program through these educational programs. Doing this would increase awareness of the NNC program among residents and, more importantly, connect visual references to the Program in retail outlets to tangible healthy eating/food preparation information communicated in the various activities mentioned previously.

Observation 3: In many respects, food retailing has improved. The selection of products has increased across almost all categories including frozen and fresh produce and the overall quality of grocery items has improved.

Recommendation: The definitions of products eligible for Level 1 or Level 2 NNC subsidies should be periodically revisited in the context of northern household purchase patterns that could be determined through discussions with retailers. Commodities that could facilitate healthy diets, but are not necessarily food items, could be discussed for inclusion in the Program.

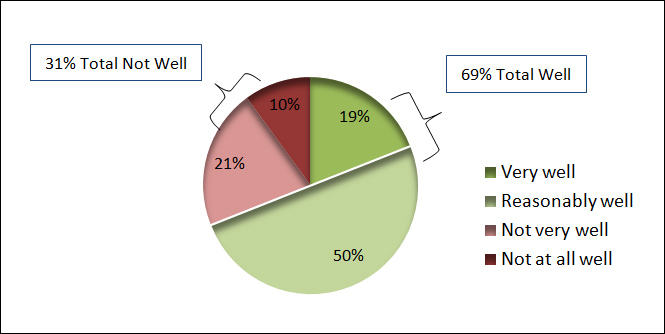

Observation 4: From in-store visitation and from consumers' commentary, it appears the incidence of spoiled or past due products is decreasing. There is still work to do in this regard, but progress has been made. Food retailing in the North appears to be functioning reasonably in the face of many logistical challenges.

Observation 5: Awareness and understanding of the NNC program among the indigenous northern population is low. When informed of the presence of NNC, residents question the extent of the subsidy and whether it applies to their local retailer. Local residents and community leaders express concerns with transparency of the Program to consumers. In many communities, this concern about whether the subsidy is being fully applied by retailers is shared at the community leadership level, which ultimately does not help communication of important NNC program details down to local residents.

Recommendation: It is important that efforts to communicate the presence and structure of the NNC program continue and, if possible, increase in retail outlets. How the Program works and on what products it applies must be continuously communicated. It would also be beneficial to the Program if residents and local community leaders were provided a more complete picture of the range of factors that contribute to the high costs of groceries in the North.

Retailers should be encouraged to be open and forthcoming with local community leaders with respect to the operation of the NNC subsidy, and answer questions that do not jeopardize proprietary information. If 'buy in' from community leaders cannot be assured, it will be difficult to maximize the community benefits of the NNC program.

In subsequent analysis, it may be useful to test the hypothesis that residents in communities with low Level 2 subsidies ($0.05) or low Level 1 subsidies (< $2) are more likely to believe the NNC subsidy is not being passed on to the consumer, compared with residents in communities with higher subsidy rates.

Observation 6: The focus on selection and improving the quality of grocery products has placed a greater resource load on the supply chain to deliver groceries to these remote communities. The NNC retailer subsidy allows retailers to seek out the most efficient resupply options to stock their shelves.

Observation 7: As populations in parts of the North are growing faster than in southern Canada, and country foods have sustainability and acceptance challenges, the demand on NNC to assist in the price tag of the healthy food basket will continue to rise.

Recommendation: Consideration should be given to increase the funding of NNC to meet this demand. NNC should at least be indexed to inflation or to changes in costs that are major contributors to the cost of food retailing in the North.

Observation 8: The NNC program is lowering prices on NNC eligible products. In this respect, the Program is working. However, costs remain high. Is lowering prices enough for local residents who are managing their households on limited and fixed budgets? We believe the answer is "No." That said, NNC is part of the solution, but not the entire solution.

Recommendation: While the food retail system in the North appears to be working, and some would observe it to be improving, food costs remain extremely high. Those with limited incomes are struggling, and increased efforts must be made to narrow the gap between disposable incomes and the price of a healthy food basket.

Observation 9: Healthy food items such as fresh fruits, vegetables and dairy are almost universally acknowledged to be coming down in price. As these are examples of the Level 1 commodities targeted by the NNC subsidy, it appears NNC works; however, consumers do not make a direct connection to this being a result of the NNC subsidy. In some communities, particularly those served by only one grocery store, residents question whether the subsidy is being passed down to them in its entirety or at all.

Recommendation: While there is considerable communication material in the stores alerting consumers to the presence of the NNC subsidy, increased efforts in communications and awareness would be beneficial. An effort to increase and vary the approaches to communicating the Program to local residents would further their understanding of how the Program works and how consumers could adjust their grocery purchases to fully benefit from the subsidy.

Having NNC references relate more directly to local meal planning and preparation courses may also be useful in improving the awareness of the Program. Similarly, assisting retailers in communicating that transportation is only part of a very complex and expensive supply chain could serve to improve NNC's awareness and provide context around the 'impact' of the subsidy.

Finally, retailers should continue and, if possible, increase their support of the educational activities of healthcare professionals in local communities in regards to nutritional eating.

Additional Observations & Recommendations beyond the scope of NNC

Observation 10: Operational costs for retail outlets are much higher in the North compared to similar operations in the South. In particular, electricity costs are a significant contributor to the total costs of operation.The kwh rates in the North can be five to ten times greater than in the South.

Recommendation: More could be done to reduce costs in the North. Alternate energy sources should be researched in order to offset or at least supplement the expensive diesel generator-powered electricity sources. Wind, hydrogen and even solar power could be considered.

Recommendation: While sea lift is relatively inexpensive in comparison to air resupply, it is still very expensive, largely because of the absence of adequate port facilities in many northern communities. Efforts should be made to develop and improve port facilities in the North. Doing so would reduce or eliminate the need for marine carriers to bring barges and tugs on board the resupply vessels to facilitate offloading.

Observation 11: Country foods are an important food source for many Northerners. They are popular and frequently consumed where available but there are questions regarding the long-term sustainability of this food source. In addition, cultural shifts are taking place in the North, with the younger generations showing signs of being less interested in living off the land than their ancestors. A decline in country food consumption will place greater reliance on the grocery retailer to supply the community's food needs.

Recommendation: Country food theoretically has the potential to reduce the demand for food being brought from the South. As such, the use of country foods should be encouraged where feasible. However, this course of action faces challenges in terms of sustainability and acceptance from future generations. Some researchers have proposed looking at the "Greenland model" where country foods go straight to local markets. There may be some very valid reasons why such an approach would not be appropriate for northern Canada, but research into that model may be worthwhile.

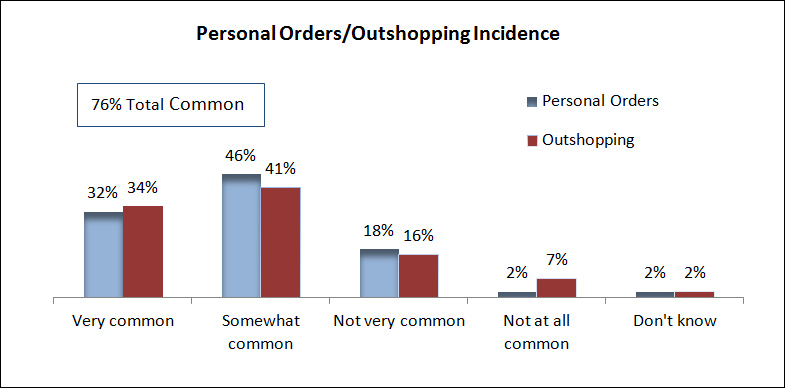

Observation 12: Shopping outside of the community store, whether via phone or internet order shipped into the community or consumers travelling to shop outside the community and bringing goods back into the community is a common activity in almost all northern communities. The extent of this varies depending on transportation availability and access to credit by consumers in the community. Local retailers are fully aware of the use of shopping alternatives to the local store but at this point do not feel it has a significant impact on their business activity.

One possible unintended consequence of the shift from Food Mail Program to NNC may be an increase in physically shopping outside the community. During this study some individuals suggested that in the past, shoppers got quite adept at bringing a wide variety of commodities into the community through the Food Mail Program. With its narrower list of eligible commodities, NNC may have prompted a number of the shoppers to move to physically shopping outside the community for items not covered by the NNC subsidy. As one resident indicated, "I'm no longer allowed to go through Food Mail. That is why I go to Wal-Mart."

Observation 13: Anecdotally, residents raise concerns that groceries are more expensive and service levels lower in communities served by one grocery store. While residents in a community served by only one grocery store may advocate strongly for the need for a second grocery retailer to "keep the other guy honest," the concerns regarding pricing appear no less intense in the community served by multiple grocery outlets. The challenge of prices is not one solved by increased competition. In fact, the high fixed costs of operating in the North may contribute to higher prices if too many retailers chase a small and isolated market.

Objective of Study

Nutrition North Canada (NNC), within Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC), tendered a request for research services to provide an overview of the nature of grocery retailing in isolated northern communities and specifically, an examination of the retail situation in the 103 communities served by the Nutrition North Canada Program.

The Statement of Work requires a comprehensive review of:

- The types of retail operations;

- The demographics of the markets in which such retailers operate;

- The nature of competitive forces in northern food markets; and

- The contribution of food retail outlets to the local economy (e.g., employment, community infrastructure and economic development).

The Statement of Work also included a request to review an earlier study The Food Retailing Structure of the Northwest Territories conducted by D. H. Green, and M. B. Green, in 1986 and to provide comparisons to current retailing conditions . It should be noted, the 1986 study was limited to the area that is now the Northwest Territories (NT) and Nunavut (NU), whereas this study addresses the entire NNC program area. In addition, retailing operations discussed in the 1986 study included communities with year round surface transportation access, whereas the NNC communities face more complex and challenging access.

Methodology

This study involves a number of different data collection methodologies. This section provides a brief outline of the various methodologies employed in this study. A more detailed examination of the methodology and source data is included in Appendix 2.

Primary Data Sources

Online Survey with Grocery Store Managers

NRG conducted an online survey with a sampling of grocery store retail managers. All grocery retailers in NNC-eligible communities that could be identified (approximately 131) were contacted to conduct an online survey. The online survey with store managers achieved a participation rate of approximately 75%.

One-On-One In-Depth Interviews

In-depth interviews were held with senior officials from the Northern Store, Arctic Co-op, Stanton's and the Fédération des cooperatives du Nouveau-Québec (FCNQ), as well as several companies active in supplying personal orders. Representatives from several airlines that provide air freight services into the North were also interviewed.

Community Case Studies

NRG Researchers visited 10 communities and conducted in-person interviews and store visits, spending a minimum of 2 to 4 days in each community gathering data.

Though a cluster analysis approach and further refinement through discussion with NNC staff, the following communities were identified for the community profile phase:

| Province/Territory | Community |

|---|---|

| Northwest Territories (NT) | Aklavik |

| Nunavut (NU) | Iqaluit; Arviat; Igloolik |

| Manitoba (MB) | Garden Hill; Lac Brochet |

| Ontario (ON) | Fort Severn |

| Quebec (QC) | Puvirnituq; Quaqtaq |

| Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) | Rigolet |

In each community, individuals or groups targeted for interviews included the following:

- Focus groups among a sample of local consumersFootnote 1, and

- In-person discussions with stakeholders in the community, particularly those involved in food retail, local government, community economic development, education and health services.

Secondary Data Sources

Prior to starting interviews, NRG Researchers conducted a literature review of existing research. An Excel database was built that was subsequently updated with demographic, socio-economic, community infrastructure, transportation and retail infrastructure data. This was compiled for each NNC-eligible community.

The NNC Program and the Northern Retail Environment

The NNC Program

The Government of Canada introduced the NNC program on April 1, 2011. The Program is a retailer-based subsidy that is designed to reduce the cost to northern consumers of perishable, nutritious food. NNC replaced the Food Mail Program which was a direct transportation subsidy administered by Canada Post. Including both the Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada (AANDC) and Health Canada portions, the NNC program currently operates within a set annual budget of $60 million.

NNC supports the shipment, sale, and consumption of perishable, nutritious food in 103 isolated communities across northern Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Labrador, as well as eligible communities in Northwest Territories, YukonFootnote 2 and Nunavut. Perishable foods can be fresh, frozen, refrigerated or have a shelf life of less than one year. NNC-eligible foods must be shipped by air.

To be eligible for the subsidy, communities must lack year-round surface transportation (i.e., no permanent road, rail or marine access). In addition, the community must have participated in the previous Food Mail Program.

Under NNC, a subsidy is paid directly to registered northern retailers and southern suppliers based on the actual weight of eligible foods shipped to these 103 northern communities. The suppliers and retailers participating in the Program are northern retailers and southern wholesalers and suppliers who have signed contribution agreements with AANDC agreeing to certain conditions of accountability and transparency established by NNC. Furthermore, the Program participants are required to pass along the full subsidy to their customers.

Some commercial and social institutions in eligible communities are also eligible for the subsidy, as are individuals who obtain their food through personal or direct orders to registered southern suppliers. Unlike with the Food Mail Program, under NNC, northern retailers and southern suppliers are required to make their own arrangements with the airlines servicing the North.

The subsidy is paid directly to the retailer based on administrative information (invoices, waybills, etc.) submitted to the government for subsidy reimbursement. Consumers are able to see their community's subsidy per kilogram rate on the bottom of each cash register receipt, and the subsidy reduction must be made visible on their invoice if ordering directly from a southern supplier.

NNC Service Area Profile

The 103 NNC-eligible communities collectively contain an approximate total population of 93,700, based on available Statistics Canada 2011 Census data (or other sources where available).

The NNC-eligible population (93,700) is located in small communities across approximately 4.3 million sq. kilometres. The largest NNC-eligible communities are Iqaluit, NU with a population of 6,699, followed by the Manitoba Island Lakes communities of St. Theresa Point (2,871) and Garden Hill (2,776), and Rankin Inlet, NU with a population of 2,577 (according to the latest census data). The smallest NNC communities are Trout Lake, NT(92) and Sachs Harbour, NT(112).

The population of the NNC region may be small, but it is growing. Between 2006 and 2011, the population growth rate in areas containing eligible communities was 6.2% versus 5.9% nationally (Census 2006, 2011). The compounded annual rate for the same communities is approximately 1.21% in comparison to the national rate of 1.15%. Nunavut and Nunavik, which account for 80% of the entire weight of foods subsidized, have higher rates of population growth at 1.5% and 2.3% per year, respectively.

In the Green report, Food Retailing Structure in the Northwest Territories, prepared in 1986, the population of the study region (before the division of the Northwest Territories to create Nunavut) was estimated to be 50,000. Today the population of the same region (NT and NU) is 73,370 according to 2011 census data — a 46% increase.

Of the total population in the NNC-eligible area, it is estimated that 90% identify as Aboriginal, according to the 2011 Household Survey.

All 103 communities lack year-round road, rail or marine access, which is one of the criteria for program eligibility. They are served by air transportation year-round, and at various times of year the communities have either winter ice road access or are able to receive resupply visits by ships, ferries or barges. Of the 103 communities, about 44 are served by road (mainly winter). These communities are mainly in the northern regions of Manitoba, Saskatchewan or Ontario. Sealift serves about 50 communities. These communities are mainly in Nunavut, although Nunavik, Northwest Territories and the Labrador coast also are served by this mode in the ice-free season. Ferry service (Labrador) also supplements resupply for some communities, bringing the number of communities with water resupply to about 60. A handful of communities (4) mainly in northern Northwest Territories appear to be served by ice roads and then by barge lift in the ice-free season.

Other traits are summarized in the following table. About one-half (48 of 103) are communities with only a single food source retailer. Air service is variable, with 56 of the 103 communities receiving air service at least 4 times per week. Most communities' runways are less than 3550 feet in length, and very few are paved.

| Attribute | Attribute | # of Communities | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Northern population | 229,822 | Avg. Runway Length | |

| Total pop. NNC-eligible (103) | 93,700 | <2300 ft. | 6 out of 103 |

| Single retailer community | 48 out 103 | 2300 ft. – 3550 ft. | 51 out 103 |

| Transportation Access | 3551 ft. to 4999 ft. | 25 out of 103 | |

| NNC Comm.'s served by Ship/Ferry | 60 out of 103 | >5,000 ft. | 7 out of 103 |

| NNC Comm.'s served by Winter Road | 50 out of 103 | Runway Composition | |

| Air Service Frequency | Paved, asphalt | 8 out of 103 | |

| Air service 4 or more times a week | 56 out of 103 | Gravel, crushed rock, dirt | 90 out of 103 |

| Airport not in communityFootnote 3 | 5 out 103 |

Northern Retailing Overview

131 grocery retail stores were identified as operating in the NNC-eligible communities. It should be noted that this number may be a slightly low approximation as some independent stores are quite small and difficult to identify through conventional sources.

Retailers operating in the North may be categorized several ways. NNC categorizes them based on their corporate structure, as follows:

- Private corporation (The North West Company (NWC)) – 67 Northern or NorthMart stores

- Co-operatives (Arctic Co-op Limited (ACL); La Federation des Co-operatives du Nouveau Quebec (FCNQ) and Stanton's) – 46 stores

- Independents – 18 stores

They may also be categorized by size:

- Two major retail chains (NWC and ACL), accounting for 97 stores

- 19 regional chains (Stanton's (2), FCNQ (14) and Big Land Grocery (3) across Northwest Territories, Quebec (Nunavik) and Labrador respectively

- Approximately 15 sole proprietor independent grocers

The NWC also operates nine convenience style stores under the QuickStop banner in NNC-eligible communities. These communities are:

- Nunavut – Pangnirtung, Iqaluit, Rankin Inlet, Arviat, Baker Lake, Cambridge Bay and Kugluktuk

- Northern Ontario – Attawapiskat and Pikangikum

A short summary of each of the retailers in NNC-eligible communities follows.

The North West Company

The North West Company has a long history of operating in Canada's north tracing back to 1668. Some communities have had a store presence for over 200 years. The North West Company's stores offer a broad range of products and services with an emphasis on food.

The North West Company also operates grocery retailing operations in remote communities in Alaska (AC Value) as well as on islands in the Caribbean and the South Pacific (Cost-U-Less). The company also operates 31 Giant Tiger stores across western Canada. The Giant Tiger brand is a general merchandise store in terms of product mix, compared to the other retail operations. The North West Company's mission is to be a trusted community store.

In Canada's north, the company currently operates under three banners (The Northern Store, NorthMart and Quick Stop convenience stores). The majority of its operations are branded under the Northern Store (122 stores in total, 68 which are located in NNC-eligible communities). North West Company operates six stores under the NorthMart brand of which one, located in Iqaluit, is in an NNC-eligible community. The NorthMart stores are larger retail operations with more additional non-grocery related amenities typically provided. Finally, there are 17 QuickStop convenience stores that typically operate in larger communities and serve as a second outlet to an existing North West Company store.

In total, between Northern Stores, NorthMart and QuickStop stores, the North West Company operates approximately 724,000 of retail sq. ft. across northern Canada. The average Northern Store size (retail space) is slightly less than 5,700 sq. ft., but this does vary considerably between communities. In addition to the provision of grocery food products, Northern Stores provide an array on non-grocery related product services such as financial services, tax preparation, general merchandise and clothing.

The North West Company's head office and primary hub of its northern Canadian retail operations is in Winnipeg, where it maintains a 248,000 sq. ft. warehouse for its inventory and distribution activities. Some northern resupply activity also occurs out of Edmonton, Ottawa and Montreal. The North West Company employs approximately 3,000 people as part of its Northern Store/NorthMart store network, with the vast majority of these individuals being residents from the local northern communities.

The North West Company, through its Northern and NorthMart stores, is a registered retail participant in the NNC program.

Arctic Co-operatives Limited

The Arctic Co-operatives Limited was officially founded in 1972 and amalgamated as an entity in 1982. However, its Co-operative roots date back to the 1950s in Canada's north. It is part of the broader Co-op community that operates across Canada. The Arctic Co-op operates a total of 32 stores in Canada's north, mostly under the Arctic Co-op banner and one identified as Arctic Ventures Marketplace (a recent acquisition in Iqaluit). Of Arctic Co-op's 32 stores, 30 are located in NNC-eligible communities.

In addition to retailing groceries in communities across the North, the Co-ops provide hotel services (Inns North), cable operations, fuel services, taxis, construction, outfitting, arts and crafts production and property rentals. All these activities—grocery and non-grocery—result in Arctic Co-op being an important service provider in the communities where it operates.

The central role of Arctic Co-op is to co-ordinate the resources and combined purchasing power of the local Co-operatives in a manner that will enable them to provide operational and technical support services to their members in an economically viable manner.

The mission of Arctic Co-operatives Limited is to be the vehicle for service to, and co-operation among, the multi-purpose co-operative businesses in Canada's north, by providing leadership and expertise to develop and safeguard the ownership participation of Member Owners in the business and commerce of their territory.

Structurally, each community where an Arctic Co-op operates is its own community owned Co-operative. Residents of the community join the Co-operative as members and are able to share in the profits of the store at the end of the year. There are some advantages to this model from a community standpoint. However, the more community-based decision format can also present challenges in terms of generating consistent system-wide outcomes.

The company's central office and hub of distribution operations is in Winnipeg. All of Arctic Co-op's stores are located in Northwest Territories and Nunavut. It employs approximately 1,000 people, with most residing in remote northern communities.

The Co-op is a registered retail participant in the NNC program.

Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau Québec

La Fédération des Coopératives du Nouveau Québec (FCNQ) is a grocery retailing Co-operative that operates solely in the Nunavik region of northern Quebec. It consists of 14 stores, all of which are located in NNC-eligible communities. The FCNQ was incorporated in 1967. The mission of the Co-operative is provided below.

The purpose of the Co-op movement is to get its members to work on their own development through social and economic activities that are financially sustainable. The purpose of the Federation is to support the affiliated Co-ops in their efforts to work on their own development.

The Co-op is involved in more than just grocery retailing. Its other activities in communities include:

- Banking, post offices, cable TV and Internet services

- Management training, staff development and auditing service

- Marketing Inuit art across Canada and around the world

- Operating hotels, a travel agency, and hunting and fishing camps

- Bulk storage and distribution of crucial oil & fuel supplies

- Construction projects in Nunavik for housing, schools, etc.

The Co-operative movement is the largest non-government employer in Nunavik, with over 260 full-time and 50 seasonal employees in the region and 120 full-time employees in Montreal. The FCNQ central office is located in Montreal.

The FCNQ is a registered retail participant in the NNC program.

Stanton Group Limited

The Stanton Group Ltd. is an Inuit-owned organization and is a registered retail participant of the NNC program. Its central base of operations is out Inuvik, NT. Its grocery retailing operation consists of 3 stores—located in Inuvik, Aklavik and Tuktoyaktuk. The latter two are NNC-eligible communities.

The Inuvialuit Development Corporation, owner of the Stanton Group, is a diversified investment, venture capital and management holding company, wholly owned by the Inuvialuit Regional Corporation. The organization's goal is to have full Inuvialuit participation in the northern Canadian economy and integration into Canadian society through development of an adequate level of economic self-reliance and a solid economic base. The Inuvialuit Development Corporation was incorporated in 1977 and is one hundred percent Inuvialuit owned.

Its grocery operations in Northwest Territories consist of the following facilities:

- 15,000 square foot warehouse in Inuvik;

- 7,000 square foot retail space in Inuvik;

- 2 outlying retail outlets - Tuktoyaktuk, Aklavik; and

- Full line of delivery vehicles in addition to a logistical coordination center in Inuvik.

The Inuvialuit Development Corporation is also diversified and has operating interests in two Northwest Territories airlines. Aklak Air offers scheduled and chartered passenger and freight service across the western Arctic. Canadian North is an airline owned equally by the Inuvialuit of the Western Arctic and the Inuit of Nunavut.

Its hubs of operations are in Edmonton and Yellowknife in terms of accessing grocery products from the South.

Big Land Grocery

Big Land Grocery, with three stores, is owned by the Labrador Development Corporation. Big Land Grocery operates stores in the Labrador communities of Hopevale, Nain and Makkovik, all of which are NNC-eligible communities. Big Land Grocery is a registered retail participant in the NNC program.

Outshopping

For the purpose this study, outshopping is defined as purchasing items outside of the local physical store. This includes individuals travelling outside of the community to neighbouring towns on winter roads, ferries or air. It also includes purchasing items from the internet or phone and having it delivered via barge, truck, ferry or air. Outshopping also includes purchasing goods from suppliers that come into the community to sell their items.

NNC Direct / Personal Order Suppliers

Residents in the North have the opportunity to order items from among 18 NNC registered southern suppliers. Individuals ("personal orders"), social institutions (e.g., schools, daycares) commercial establishments and even small retailers (e.g., hotels, restaurants) are able to place direct orders with their chosen supplier and transport the order to their community. These NNC registered southern suppliers sell both subsidized and non-subsidized items. Some companies, in addition to basic groceries, specialize in the provision of particular products such as organic foods or meat packs to customers. NNC registered suppliers are required to pass on the subsidy on all items that are identified on the NNC list of Subsidized Foods. When NNC-eligible products are ordered, the savings is calculated for the weight of the subsidized items and indicated on the customer's invoice.

Direct order supplier businesses are set up in several different ways in terms of their structure and operations. Most registered direct order companies are located in a southern city or town (at least far enough south for all weather road access). One company was identified as having a satellite office in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut. The purpose of the office was said to have been established to better assist its customers.

Some companies operate like grocery distributors with fairly large warehouse space, coolers and freezers. These organizations have sophisticated order assembly and packing areas. A few companies visited as part of this study (Arctic Buying Company, Harris Meats) maintained from 9 to 15 staff, depending on the level of activity.

Other companies are much smaller in nature and typically associated with a larger traditional grocery retailing operation. The personal order business is an offshoot of the grocery store activity. Typically, the direct order part of the business has space at the rear of the store and relies on the logistics of the main grocery retail operation to support the direct order requirements.

Some suppliers are almost exclusively serving individual customers while others are involved in supplying commercial customers (restaurants, hotels, outfitters), corporate customers (mining camps) and government events (conferences). It should be noted that hotels, restaurants and social institutions such as day cares are eligible to access the NNC subsidy, but commercial organizations, such as mining operations, and government agencies are not eligible for the NNC subsidy. A list of recipients that are not eligible to claim the subsidy is listed on the Nutrition North Canada program website.

In interviews conducted with several suppliers, it was reported that for Nunavut and Nunavik the most frequent individual customer tended to be a transplanted southerner working in the North. In northern Manitoba and Ontario, however, this was less likely to be the case, as indigenous locals and transplants were equally likely to be using the services of a personal order supplier.

Based on interviews, and from evidence gathered in actual communities, most order companies have particular regions of focus. This focus is in part influenced by transportation logistics and the ability to find efficiencies in routing, trans-shipping and favourable freight contracts for some communities. Additionally, some companies may focus on certain areas because the business owners may have community connections which facilitate a good working relationship with particular customers.

The more active direct order companies negotiate freight rates with air carriers to transport their goods to the North. Other firms simply pass this cost to the customer. Some companies also organize large orders (crates) for customers that are barged in during the annual summer resupply period, although these shipments or orders would not be eligible for the NNC subsidy, which can only be applied to eligible items transported by air.

While NNC collects data on the weight of eligible items subsidized under NNC's direct order provision, it is not possible to accurately develop a picture of how large the direct order business is in terms of volume of groceries being sold into the North outside of NNC. One airline active in northern freight transportation estimated that they currently transport approximately 10 million lbs of personal order freight annually into northern Manitoba. The company added that this volume of business is down from over 11 million lbs about 5 years ago. The decline was attributed to the change to a narrower list of food products eligible for a subsidy following the transition from the Food Mail Program to NNC. As noted earlier in this report, local residents appear to be resorting to more shopping physically outside the community as opposed to flying on direct orders.

Cost Drivers of Retailing Groceries in the North

Transportation

Transportation is a significant factor that influences the differential in the price of groceries between northern and southern retail outlets.

One key element is that, unlike most southern grocery retailers, stores operating in the North are responsible for the transportation of their product and merchandise to their store. In the South, the supplier assumes the cost of transporting their product to the retailer for sale. Not only is transportation to northern store locations costly, it is also an additional direct cost borne by northern store locations, whereas it is not generally a cost line item exposed to management of southern retail operations.

Major northern retail chains must also provide the necessary supporting infrastructure to efficiently accomplish this task because they are responsible for the transportation to their network. This involves significant warehousing in southern locations to receive goods from suppliers, organize them and ship them out to various points for distribution in the North. For example, the North West Company maintains a 248,000 sq. ft. warehouse complex in Winnipeg. There are costs associated with maintaining this infrastructure, in addition to the actual costs associated with handling and moving the product from the warehouse to store, a discussion of which follows.

Several factors increase the cost of freight movement. These are the mode of transportation, the distance travelled and the number of times the freight is handled or 'touched' along the way. The actual number of times an item is handled in a cross-dock or trans-shipping process may be a greater factor in increasing costs than is the actual distance travelled. On a tonne-kilometre basis, ocean freight is the least expensive freight transportation mode, whereas air freight is the most expensive.

For acceptance under the NNC program, communities must lack year-round surface transportation (i.e., no permanent road, rail or marine access). In all 103 NNC-eligible communities, air transportation is critical to the ongoing resupply of groceries, particularly for perishable items such as produce, meats and dairy.

An annual resupply is typically conducted, either in the ice-free period in the summer when barges and ferries are able to transport goods to a community, or in the winter months when a winter (ice) road can be constructed and operated. These seasonal resupplies are mainly used to move bulky, heavy or non-perishable items. As such, the NNC subsidy is not applicable.

Whether by air freight, ship, barge, or trucking, it is more expensive to transport goods to a remote northern community. Retailers themselves or the organizations they belong to—North West Company or Co-ops — are cautious about sharing precise freight costs for transporting goods to their stores for competitive reasons, but from the various interviews conducted over the course of the study some information regarding the costs of shipping to an isolated northern environment is provided in the following sections. In addition, where possible, comparisons to shipping in a southern environment are provided for contextual purposes.

Air Freight

A senior Perimeter Air staff member who is active in shipping freight into northern Manitoba communities, including many NNC-eligible communities, estimated that the cost is approximately 30% higher than shipping freight a comparable distance in the South. Calm Air, another prominent northern airline, did not provide an actual percentage, but firmly agreed that transporting freight to the North was comparatively more expensive than freighting within the South. Calm Air is active in flying out of Winnipeg servicing routes in Nunavut.

Reasons provided by the air carriers as to why it costs more to move freight by air in the North compared to the same distance in the South are provided below:

- Staffing: The pilots flying northern routes are paid more – close to 20% in some cases. As well, ground crews are required in northern locations to be paid at a higher rate than a comparable position in the South. Calm Air maintains its head office in Thompson, Manitoba. As a result, the company pays more for staffing certain positions in its Thompson operations.

- Fuel: Fuel is more expensive in the North. Planes almost always have to refuel in the North for the southbound return trip. This is due to the great distances travelled and/or the decision not to carry excess fuel in order to facilitate greater freight capacity. The fuel stored in various remote communities is trucked in on winter roads or barged in, and is therefore more expensive than fuel staged in the South. In addition, the fuel must be purchased well in advance of consumption and stored in significant quantities at the airports.

- Airport infrastructure maintained by airlines in the North: Infrastructure is more costly to build and maintain in the North. Also, timelines for building infrastructure in the North can be two or three times longer than in the South, which delays its revenue-generating capacity.

- Runways: The length of the runways and their predominantly gravel construction increases the operating costs for airlines flying these routes. Most runways in the NNC-eligible communities are approximately 3500 ft. in length. This is shorter than most runways in the South and a shorter runway requires additional braking when landing, increasing the frequency of brake maintenance. For most large turbo prop or jet aircraft, the gravel runways also necessitate the installation of gravel landing kit. Gravel kits cost between $700,000 to $1 million to purchase and install.

A final observation about the costs associated with air resupply is that there was no ability, from an air service perspective, to achieve any economies of scale as is possible in southern markets. This is primarily due to:

- Small populations in the communities being served;

- Limited runway lengths; and

- Low load factor potential for flights with origin/destination pairs within the North.

Apart from Iqaluit, which has the population base and the location to serve as a hub for points further north, the planes serving NNC communities are smaller turboprop aircraft, often in a combination passenger and freighter configuration (Combi). The volume of perishable freight required in these communities is relatively small, and the Combi configuration is efficient due to its flexibility. On any given flight, the number of passengers and freight load can be quite variable. By having flexible bulkheads, the passenger cabin can be relatively quickly reconfigured to maximize the use of cabin space, allowing for sufficient seating for passengers while simultaneously maximizing floor space for cargo (bulk or palletized). Essentially, the Combi configuration allows each flight to be customized to meet the needs of the flight's passenger and freight load. In some airframes, movement of the bulkhead and adding or removing seats can be readily accomplished in a matter of hours.

However, while efficient on a flight-specific basis, as a fleet-wide modification, the Combi is not as cost-effective as larger freight-only aircraft operating in conjunction with passenger aircraft with belly cargo. The reality is that load factors and freight demand in the North's thin markets do not warrant this more cost-effective fleet make-up.

There are few circumstances where northern communities can take advantage of the most efficient fleet configuration. Iqaluit, as a major northern hub, utilizes B737 Combi aircraft in links with the South. Iqaluit is also served by an all-freight B767. The typical Iqaluit-Ottawa route uses either a passenger B737 or a B737 Combi, depending on the passenger load requirements. Iqaluit has a high government presence at both the territorial and federal level, contributing to a frequent need for a passenger-configured B737. In such instances, freight, including food items for northern communities, is held back for the next flight. In thin, uneven markets, passenger travel and air freight can often be in a competitive situation, and freight always loses that competition.

Trucking - Winter Roads

Another critical resupply method for the NNC-eligible communities is the seasonal opportunity of winter roads or ice roads. Winter roads are particularly important for the resupply of NNC-eligible communities located in the northern regions of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Ontario and a few locations in the North West Territories.

The ice road season is the primary resupply time for the store's non-perishable grocery and non-food household items—canned goods, packaged dry goods, bottled beverages, paper products and cleaning supplies for example.

The goal of the seasonal resupply for remote stores is to bring in enough stock to last the store until the next season resupply period (up to 12 months). In reality, this is not always possible because some grocery items have suggested Best Before Dates (BBD) that limit the time they are saleable.

As with air freight, this research provides evidence that resupply into remote northern communities by winter road is more expensive than a similar trucking resupply effort between southern locations. Based on retailer and local government interviews, rate differentials can be quite significant depending on the location being served. The following are some examples of differing freight charges:

- Winnipeg to Edmonton, AB – approx. $1,200 (1350 kms)

- Winnipeg to Thompson, MB – approx. $3,500 (770 kms)

- Winnipeg to Garden Hill, MB – approx. $6,520 (1070 kms of which 300 kms winter road)

- Winnipeg to Fort Severn, ON – approx. $16,000 (1700 kms of which 700 kms are winter road)

The previous examples, in particular the freight charges for Winnipeg to Edmonton (two southern locales) versus going north, demonstrate the increased hauling charges. The reasons for the higher northern hauling charges are:

- The inability to pick up a return or backhaul once reaching the final destination in the North. In the first example in the previous list, it would be normal for the truck, once reaching Edmonton, to pick up another load and haul that to a destination out of Edmonton. This is a rarity for northern hauls, so the truck must return to its original southern destination empty and at a cost to the original vendor.

- The pay for truckers travelling winter roads is higher than truckers on all weather roads, in order to account for risks with winter road trucking. Mishaps are infrequent, but they do occur and can be severe, given the remoteness of the areas travelled. In addition, due to safety reasons, truckers travelling on winter roads are only allowed to travel between 20 to 30 KM/hr. This lengthens the duration of trips considerably and adds to the cost.

- Refueling during long winter road trips (i.e., Fort Severn) is more costly compared to long southern all weather road trips. On long winter road trips, it is common for trucks to travel in a convoy with several trucks hauling fuel. This provides a fuel source along the trip, as well as fuel support in case of mechanical breakdowns or mishaps. The need to travel with extra trucks with the sole purpose of carrying fuel for the convoy is rare in the South, and is another example of expensive accommodations that need to be made for northern resupply.

- Based on interviews, some winter roads can be very rough and, as a result, hard on trucks and trailers. This causes increased maintenance activity that, while borne by the trucking company, is assumed by retailers to be built into the winter road hauling freight rate.

Even with the increased costs illustrated previously, retailers still say that trucking is one of the most affordable means of resupplying a store on a per pound basis. Typically, a store requires three to five semi trailer deliveries of grocery and merchandise items to supply their needs beyond the end of the winter road season.

Ship, Barge – Sealift

Resupply in the summer months (July – September) by boat is critically important for NNC-eligible communities located in Nunavut, Northern Quebec (Nunavik), parts of Northwest Territories and Labrador. As with winter roads, this is an opportunity for retail stores in these communities to stock up their warehouse with durable goods that should, for the most part, last through to next year's resupply period (again subject to BBD issues). Marine resupply is more affordable than via air cargo.

Some factors make marine supply more expensive in the North than between ports located in southern communities. The staging or loading of the ships is a more involved and complicated process in the North. Usually the ships are making multiple ports of call on a trip, so freight has to be loaded in a manner that can be efficiently accessed in the order of communities visited. Complicating the loading of resupply orders for retail stores, a considerable amount of personal orders and non-grocery supplies are included for the community.

Another cost driver of the summer marine resupply process is associated with inconsistent (or absent) harbour and docking facilities. Some communities, for example many in Nunavik, have reasonably good docking facilities with relatively efficient unloading. However, other communities served via ship, particularly those further north, are located in areas where the ocean floor offshore drops off very gradually. There are few natural harbours further north meaning, in conjunction with extreme tides, the sealift must operate mostly without port infrastructure in the traditional sense.

A common but complex approach is the use of lightering tugs and barges. The ocean-going sealift vessel anchors offshore and items are offloaded onto barges alongside the sealift vessel. Lightering tugs then push the barges to shore and ramps are laid down, allowing front-end loaders to remove the freight for on-shore warehousing. The following are a number of images that describe the process. It should be reinforced that this complex and time-consuming procedure is not required at ports with well-established infrastructure.

Off-loading Barges and Lightering Tugs

Source: Desgagnés Transarctik Inc.

Lightering Tug moving Barge to Shore

Source: Desgagnés Transarctik Inc.

Unloading Barges on Iqaluit Shoreline

Source: Desgagnés Transarctik Inc.

Barge handling is a lengthy process that is sometimes delayed due to difficult weather conditions. This adds costs that are reflected in the shipping rates. As stated earlier, marine is considered the least expensive freight mode on a tonne-kilometre basis. However, as was also pointed out, trans-shipping (transferring goods from one transportation mode to another) contributes dramatically to costs along the supply chain. While sealift is still the most cost-effective mode, the adaptations required to make sealift work in the North cut deeply into the cost savings inherent in that mode.

While climate change may have increased the number of sealift cycles within a season, there are downsides. It has been reported that shorelines and freight lay down areas have become softer, resulting in greater offloading challenges, and the increased tendency to "sink a loader" in the mud.

Distance to Market

Regardless of transportation mode, another factor that can increase transportation costs is the distance the freight must travel from source to market.

If one were to take the centrally located city of Winnipeg, MB as a starting point (also home to head offices of the North West Company and Arctic Co-op which together operate 95 stores in NNC-eligible communities), this would be the distance from it to reach the northern markets.

Arctic Co-op Limited

- Winnipeg to Arviat, NU(closest) - 1,340 kms

- Winnipeg to Rankin Inlet, NU - 2,465 kms

- Winnipeg to Grise Fiord, NU (furthest) - 3,020 kms

North West Company

- Winnipeg to Little Grand Rapids, MB (closest) - 275 kms

- Winnipeg to Iqaluit, NU - 2,300 kms

- Winnipeg to Norman Wells, NT- 2,425 kms

- Winnipeg to Old Crow,YK (furthest) - 3,060 kms

The resupply distances are considerable in most instances, and even if one was incorporating the most economical method of resupply, which is not the case, the costs will be higher managing a store network spread across the North.

Freight Handling – the Number of Touches

Retailers said in interviews that each time a product is handled or 'touched' before getting to the sales floor, the cost of getting the product to market increases. Retailers strive to limit the handling of a product through shipping in larger volumes and automating the handling processes as much as possible.

In the practice of northern grocery retailing, the same rule applies; however, the logistics of supplying remote communities requires a much greater degree of handling than in the South. The table at the top of the next page illustrates the handling requirements of perishable goods being transported to several northern markets. A southern store example is provided as context.

| Southern Store | Igloolik, NU | Lac Brochet, MB |

|---|---|---|

| Freight is loaded and departs supplier | Freight is loaded and departs supplier | Freight is loaded and departs supplier |

| Arrives at store and is unloaded | Arrives at retailers warehouse and is unloaded | Arrives at retailers warehouse and is unloaded |

| Product is moved to store shelf for sale | Product is loaded on a truck and driven to Winnipeg airport | Product is loaded on a truck and driven to Thompson airport |

| Freight is unloaded at the airport | Freight is unloaded at the airport | |

| Freight is loaded onto an aircraft bound for Iqaluit | Freight is loaded onto an aircraft bound for Lac Brochet | |

| Freight is unloaded at Iqaluit airport | Freight arrives at Lac Brochet airport and is unloaded | |

| Freight is loaded on to a different aircraft bound for Igloolik | Freight is loaded on to trucks and driven to store | |

| Freight arrives at Igloolik airport and is unloaded | Freight is unloaded at store | |

| Freight is loaded on trucks and driven to store | Freights is moved to store shelf for sale | |

| Freight is unloaded at store | no value | |

| Freight is moved to store shelf for sale | ||

| 3 total touches | 11 total touches | 9 total touches |

As the previous table illustrates, grocery products must be handled three or four times more between receipt from the supplier and stocking to the shelf in the North.

Transportation Summary

The preceding pages describe in some detail the additional effort and costs associated with supplying grocery products to stores in isolated northern communities. The table illustrates in dollars what this can amount to in transportation costs. To provide context, an all weather road served store (La Ronge, SK) is provided. These numbers have been provided by the North West Company.

| Community | Size of Store | Transportation (freight) Costs 2012 |

|---|---|---|

| Baker Lake, NU | 13,290 sq. ft. | $2.07 million |

| Iqaluit (NorthMart), NU | 40,988 sq. ft. | $5.41 million |

| Gjoa Haven, NU | 5,775 sq. ft. | $1.62 million |

| Fort Severn, ON | 7,800 sq. ft | $.40 million |

| La Ronge, SK (NorthMart) – All weather rd. accessible | 16,806 sq. ft. | $.33 million |

The inclusion of the transportation costs for the La Ronge, SK store provides an illustration of how a moderately sized store with all weather road freight access can be supplied for a year at significantly less expense compared to stores in isolated communities.

Bricks & Mortar

A second cost driver contributing to a higher cost of groceries in the North relates to the physical store presence in these communities. Maintaining a physical retail presence in remote northern communities is significantly more expensive than maintaining a retail presence in a southern community.

Initial construction costs of stores in remote communities are much higher and require significant logistical planning. The materials are trucked (winter) or barged (summer) into the community well in advance of the actual construction work. Much of the labour must be flown in and housed during the construction process.

In dollar terms, the North West Company indicated that the building investment in one of its southern Giant Tiger stores is about $68 a sq. ft. The building investment in its Northern Stores ranged depending on location, age and size of the store, but there were numerous examples of where this investment was well over a $100 a sq. ft. In Arviat, NU the investment in the Northern store was the equivalent to $119 a sq. ft. while in Lac Brochet, MB it was $279 a sq. ft. In Igloolik, NU the investment amounted to $155 a sq. ft. and in Aklavik, NT it is about $140 a sq. ft.

Based on interviews with retailers operating in northern communities, the general operation of a grocery retail store is more expensive in comparison to the running of a store in the South. Retailers identified three areas in particular as more expensive in the North than the South: warehouse to retail space ratios, electricity costs and repair and maintenance costs. A summary of each of these costs is provided below.

Warehouse to Retail Space Ratio

Warehousing requirements and subsequent costs are much greater in isolated northern communities. Unlike southern retail operations with the standard practice of "just in time" delivery of groceryproducts, isolated northern stores must maintain a much greater amount of stock in the community. This requirement is typically met at one time in the year when a more economical transportation mode is available. The warehouse space must be properly maintained for product storage. A significant amount of the warehouse space (typically over 60%) must be heated to prevent product from freezing. These undertakings increase the operational costs of running the store.

In a southern grocery retail situation, minimal warehousing space is required because product tends to go directly to the shelf. In discussions with retailers, NRG Researchers were informed that for every 1 sq. ft. of warehouse/loading space there is approximately 6 sq. ft. of retail floor space in the South. In the North, this ratio varies significantly, as per the following examples:

- The Northern Store in Igloolik, NU – 1 sq. ft. warehouse to 2 sq. ft. of retail.

- The FCNQ Co-op in Puvirnituq, QC - 1 sq. ft warehouse to 3 sq. ft of retail.

- The Northern Store in Rigolet, NL– 1 sq. ft. warehouse to 1 sq. ft. of retail.

Electricity Rates

Electricity costs are significantly higher in northern communities because electricity is produced by diesel generators. The following table summarizes the electricity rates experienced by stores in various northern communities. Not only are diesel generators less efficient than large power stations, but the electricity charge also bears the cost of transporting the diesel fuel to the communityFootnote 4.

| Store Location | Per Kwh rate (2014) | Per Kwh rate MB (2014) | Per Kwh rate ON (2014) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arviat, NU | $.65 kwh | $.06 kwh | $.09 kwh |

| Igloolik, NU | $.86 kwh | $.06 kwh | $.09 kwh |

| Aklavik, NT | $.42 kwh | $.06 kwh | $.09 kwh |

| Rankin Inlet, NU | $.51 kwh | $.06 kwh | $.09 kwh |

| Iqaluit, NU | $.46 kwh | $.06 kwh | $.09 kwh |

| Gjoa Haven, NU | $.76 kwh | $.06 kwh | $.09 kwh |

| Lac Brochet, MB | $.34 kwh | $.06 kwh | $.09 kwh |

In addition to higher per kilowatt rates that many northern stores are subject to, a monthly electricity demand rider is often assessed over and above the variable cost for the electricity consumed. Depending on the size of the store and warehousing being heated, the demand rate can be hundreds to several thousand of dollars a month.

To put this into perspective, the 19,220 sq. ft. Northern Store in Rankin Inlet, NU spent $384,334 on electricity costs in 2012. The similarly sized NorthMart store in La Ronge, SK (16,800 sq. ft.) is on the electricity grid and subject to a $0.09 kwh rate. This meant NorthMart spent $58,500 in 2012— almost six times less than the cost of heating and lighting the Rankin Inlet, NU store. Temperature differences resulting in varying heating needs is also a factor to be considered. The average high temperature in Rankin Inlet is -7°C, while it is +6°C in La Ronge, SK.

Repair and Maintenance Costs

Repair and mechanical maintenance are other factors that impacts the costs of northern grocery retailers compared to the southern retailers. During conversations with retailers, this was reported as a growing challenge because in response to consumer demand there has been a gradual increase in frozen and chilled products being carried in the stores. Retailers indicated that refrigeration now accounts for approximately 15% of the selling space in a typical store in the North. The increased refrigeration/freezer requirements increase the need for maintenance activity or repair incidents.

According to retailers, local mechanical repair capability is almost never available in the NNC-eligible communities. If a store does require service, a technician must be flown in and is typically required to stay at least a full day (10 hours) in community.

Following are examples of average refrigeration repair/maintenance incident costs to the northern retailers:

- Rigolet, NL - $3,900 per incident

- Lac Brochet, MB - $3,500 per incident

- Iqaluit, NU - $6,100 per incident

- Aklavik, NT - $3,500 per incident

- Baker Lake, NU - $5,800 per incident

The cost of a similar refrigeration repair/maintenance incident for a southern retailer is much lower, averaging in the hundreds of dollars, unless there is significant travel time involved.

Retailers were unable to provide a global sense of how much of their operating budget was devoted to repairs of this nature. A representative from the Nunavik cooperatives, FCNQ, indicated that their stores are encouraged to budget 3% to 4% of their overall operating budget for repairs.

Wages and Salaries

Another cost driver mentioned by retailers relates to staffing costs. Head office staff and store managers indicated that they typically have to provide a higher level of pay than for equivalent staff in the South, most notably in Nunavik and Nunavut regions. In northern Manitoba and Ontario, the differential in staffing costs is less. An FCNQ representative indicated that staff wages tend to be 15% to 20% higher for their Nunavik stores than for comparable positions in Montreal.

The wage differential between the North and South may in part be driven by the high costs of living and housing costs in the North. Looking at employment opportunities within the Government of Nunavut, there is a great range in possible remuneration. Recent job postings drawn from the Nunavut Government website (summarized in the following table) illustrate a range of remuneration, from over $55,000 to about $122,000, based upon job description. These examples are intended to be illustrative and not representative of the distribution of available positions.

| Job Description | Location | Salary | Northern Allowance | Northern Allowance as Pct of Salary | Total Income (incl Northern allowance) | FTE Total Income (incl N. allowance) based on 200 x 7.5 hr days/yr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source: Government of Nunavut | ||||||

| Janitor - Education | Arctic Bay, NU | $24.56 | $12.24 | 49.8% | $36.80 | $55,200 |

| School Secretary - Education | Kimmirut, QC | $30.84 | $9.81 | 31.8% | $40.65 | $60,975 |

| Petroleum Products Clerk - Community and Government Services | Pond Inlet, NU | $56,394 | $24,214 | 42.9% | $80,608 | no value |

| Call Centre Agent - Community and Government Services | Iqaluit, NU | $74,217 | $15,016 | 20.2% | $89,233 | no value |

| Manager, Policy and Legislation - Community and Government Services | Iqaluit, NU | no value | no value | no value | $101,498 | no value |

| Homeownership Analyst - Nunavut Housing Corporation | Arviat, NU | $86,873 to $98,592 | $21,113 | 21.4% - 24.3% | $107,986 to $119,705 | no value |

| Director, Population Health - Health | Cambridge Bay, NU | $102,556 | $19,716 | 19.2% | $122,272 | no value |

Public sector employment in the North is frequently accompanied by some "northern allowance" designed to maintain real incomes, at least at the level experienced in the South. Northern allowances are common within government positions, and appear to be "progressive", in that the allowance is higher, on a percentage basis, for job classifications associated with lower incomes.

The presence of large northern allowances (increasing effective salaries by up to 50%) illustrates that costs of living are acknowledged to be significantly higher in the North. In addition to northern allowances, subsidized housing is also made available for some job descriptions, although the housing stock appears to be tight.

With northern allowances being very common, the effects of these measures may, in fact, be incorporated into the expectations of those in the North, creating inflationary pressures on prices of goods and services. While the examples in the previous table apply to Nunavut Government employment opportunities, other employers operating in the North have to compete with these levels of remuneration.

On a number of occasions, companies operating in the North said they were out-bid for staff by the Nunavut Government. A Co-op manager in one community recounted a specific instance where he hired a local employee with skills well suited to their retail operation. However, the employee was enticed away from the Co-op by a much higher remuneration package offered by the Nunavut Government. Not wanting to lose a valued employee, the Co-op manager met the government bid. However, the Nunavut Government recruiter then raised the government's offer beyond the Co-op's ability to match. This is apparently not a rare occurrence when potential employees with a desirable skill set and work ethic present themselves. This is also not a new phenomenon, as during a 2010 presentation to a University of Manitoba conference, a northern airline management staffer reported that "We compete with (the) government for employees."

Not all citizens in the North are sought out in this fashion, and not all are offered what appear to be generous remuneration packages. As a result, there is a great potential for bi-modal income distributions, in which a large number of well-paid employees can function quite well in the expensive northern environment, but another large group are struggling. As cited in the recent Canadian Council of Canadian Academies report on aboriginal food security, "the average weekly cost for groceries across the region … was … $19,760 per year … in comparison, 49.6% of Inuit adults earned less than $20,000."Footnote 5

The bi-modal income phenomenon is not distributed evenly across the communities in the North. Larger communities with a larger percentage of "southern imports" (such as Iqaluit with 42% non-indigenous residents) have a greater potential for that income dispersion. As an air carrier employee indicated, "Government dominates the activity in this town (Iqaluit)." It is likely this dominance was not as significant prior to the creation of Nunavut as a separate territory in 1999.

Another staffing concern heard from store managers was the need to maintain a larger staff complement than normally required for a store located in the South, resulting in greater time spent on human resource (HR) issues. While not a direct cost driver, staffing and HR issues do tend to occupy a greater amount of store managers' time when operating in the North.

Spoilage and Shrinkage Losses

Product loss from spoilage or shrinkage represents another factor in which stores operating in remote northern locations are subject to situations unique to where they operate compared to grocery stores in the South. Retailers indicated product losses are higher in the North. It is worth noting that the costs of shrinkage in the North are higher than just those of the absolute volume, because with every item lost there is the additional cost associated with it being transported and stored at a higher cost than in the South.

Spoilage

Spoilage is defined as product deterioration that is expected even under the best operating conditions. It is an assumed part of operations and factored into the cost of doing business. According to a representative from North West Company, typical southern rates of spoilage make up approximately 0.4% of total sales.

Risks of spoilage are greater when retailing in isolated northern communities. The risks are greater due to:

- Time and distance to market – the travel is prolonged and at times can be rough leading to bruising. In addition, the many handlings of the product can lead to damage;

- Delays in transport due to weather conditions can lead to spoilage;

- Exposure to weather extremes – Many store managers and some consumers reported seeing fruits and vegetables touched by frost due to the transfer from plane to store. Extreme heat occasionally experienced in northern communities was also noted as a more recent problem;

- Smaller markets, with a tendency for greater variance in consumption of lower demand items, with a greater likelihood that the store will either run out of stock or have the product age on the shelf beyond its Best Before Date; and

- Best Before Date issues – unlike southern retailers, there is no recourse in terms of possibly returning this product to the manufacturer for a credit.

The last point in the preceding list warrants a more detailed discussion as it represents a particular challenge for northern retailers. Best Before Dates on dairy, fresh meats and processed foods have been utilized for grocery products for a long time and consumers are aware of the Best Before Dates when purchasing these products. Based on feedback from consumers, store managers and personal store visits, the presence of "expired" products on the shelves appears to be a declining issue in northern retail stores. Managers indicated that through careful ordering they typically do not lose much product to shelf life issues. An exception occurs occasionally when a new dairy product is introduced but does not sell well. It then must be disposed at a loss.

While the Best Before Date issue may be less of a concern than in the past, it should be noted that there are numerous misconceptions with terms such as 'Best Before' or 'expired.' The Canadian Food Inspection Agency may have clear guidelines about date labelling for terms such as 'Durable Life,' 'Best Before' dates, 'Expiration' dates or 'Use By' dates, but the consumer is woefully unaware of the distinctions. In virtually all consumer discussions involving these terms, they were perceived as interchangeable.

A stamped 'Best Before' date was perceived as the same as an 'Expiry' date. The 'Best Before' date was the most common labelling, although some items (such as infant formula) have 'Expiry' dates. In some instances, NRG researchers observed customers "stocking up" on discounted infant formula that was approaching its expiration date. When asked, the customers stated "if something is on sale, it is about to expire." Unless these customers were buying for a number of households (a possible scenario), it is possible much of the product purchased would have been used after its expiration date.

Product dating is a challenging issue for retailers in northern Canada. Store managers stated that it is difficult to manage the annual influx of inventory during the resupply period. Efforts are made to order product with as much shelf life as possible. However, problems arise when manufacturers send up in a resupply shipment product with a shorter Best Before Date than what they had requested in the order. Unlike store managers in the South who are able to send product back to the manufacturer if necessary, stores in the North do not have the same recourse.

Retail managers and head office representatives stated that it was policy to ensure that no product was on the shelves past the Best Before Date; therefore, stock was sold at a significantly reduced price as it neared its Best Before Date. This represented a profit reduction or loss for the store on that product. In-store visits confirmed this activity as there were almost always significant sales (50%) on products that were nearing their Best Before Dates.